Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri. He was a prolific writer, poet, playwright, author and activist. As a young man, Langston led a complex and adventurous life both in the United State and abroad, which undoubtedly influenced his writing style and his outpouring of work. He was a key player in the Harlem Renaissance, a collective of African-American writers, artists, performers, and activists, which included Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, Alan Locke, Claude Toomer, Josephine Baker, and Louis Armstrong.

Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri. He was a prolific writer, poet, playwright, author and activist. As a young man, Langston led a complex and adventurous life both in the United State and abroad, which undoubtedly influenced his writing style and his outpouring of work. He was a key player in the Harlem Renaissance, a collective of African-American writers, artists, performers, and activists, which included Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, Alan Locke, Claude Toomer, Josephine Baker, and Louis Armstrong.

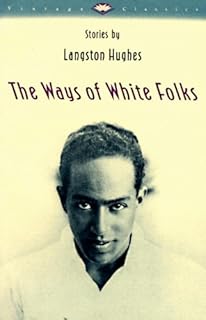

Intrigued by both the Harlem Renaissance and its key players, I found myself drawn to Hughes collection of short stories The Way of White Folks. And though it was published in 1934, I find it immensely timely in 2017.

Langston’s stories fully express the lives of black people, especially when dealing with white people, during the 1920s and ‘30s, even those so-called good liberal white people who only seemed to be on the side of “colored people.” These stories are at turns sad and humorous, and not one of them rings a false note.

The Way of White Folks consists of 14 powerful short stories. It opens with “Cora Unashamed.” Cora of the title is Cora Jenkins who lives in small town called Melton. She is considered a “Negress,” that is a polite, unassuming, and quiet colored lady. She works for the Studevants, who sadly to say, don’t treat her in a favorable manner. And Cora accepts this because due to her race and her sex, she doesn’t have much power.

Cora does everything for the Studevants. She cleans cooks, runs errands and takes care of the children. But to the Studevants, Cora is just a servant, nothing more. She should be grateful for the job.

But she is so much more than a servant. She is quietly strong. She once had a passionate love affair. And as the “Cora Unashamed” unfolds proves to be far more bold and passionate than she lets on unleashing a very surprising and interesting dénouement.

In “Home,” the protagonist, Roy Williams goes back to his home in the United States after many years of making a living as a jazz musician, traveling all over Europe. Roy contemplates how his experiences in both cultures as a black man are similar and different.

The Colony, a collective of black artists and intellectuals, is splendidly examined in the chapter called, “Rejuvenation of Joy.” These talented people convey both the good and bad of The Colony and what they face when not in their protective and inspiring community of shared experiences.

The final chapter “Father and Son” tells the tale of Colonel Thomas Norwood’s relationship with his black mistress Coralee Lewis and their biracial children. Colonel Norward takes advantage but doesn’t offer advantage to these children. And his attitude is best summed up in the dejected and heartbreaking words of his son, Bert.

“Oh, but I’m not a nigger, Colonel Norwood. I’m your son.”

Although I finished this book several days ago, I still feel them greatly. I have very little in common with Langston Hughes. I am a privileged white woman born and raised after the age of Jim Crow. Yet, I’d like to think it’s my deep well of empathy that made me love this book, but I also grew up in a small town where people still harbor the racist ideas of the white folks in this collection. When it comes to works of culture and art, we don’t only see them as they are; we also see them as we are.

But for the most part, the reason why The Way of White Folks cuts so deep is due to the book itself, and Langston’s gifted, soulful way with the English language. It is a book that will take a figurative spot within my soul, and one I can truly say is placed on my book self.