A few years ago, I reviewed a book called The Zonderling, which was about the residents of an all-women’s hotel in New York City. The Zonderling was clearly based on the Barbizon Hotel of yesteryear in Manhattan. Now before I knew about the Barbizon Hotel, I knew about Barbizon Models, and their ads found in the back pages of magazines like Seventeen and Glamour. “Be a model. Or look just like one” promised the ad copy.

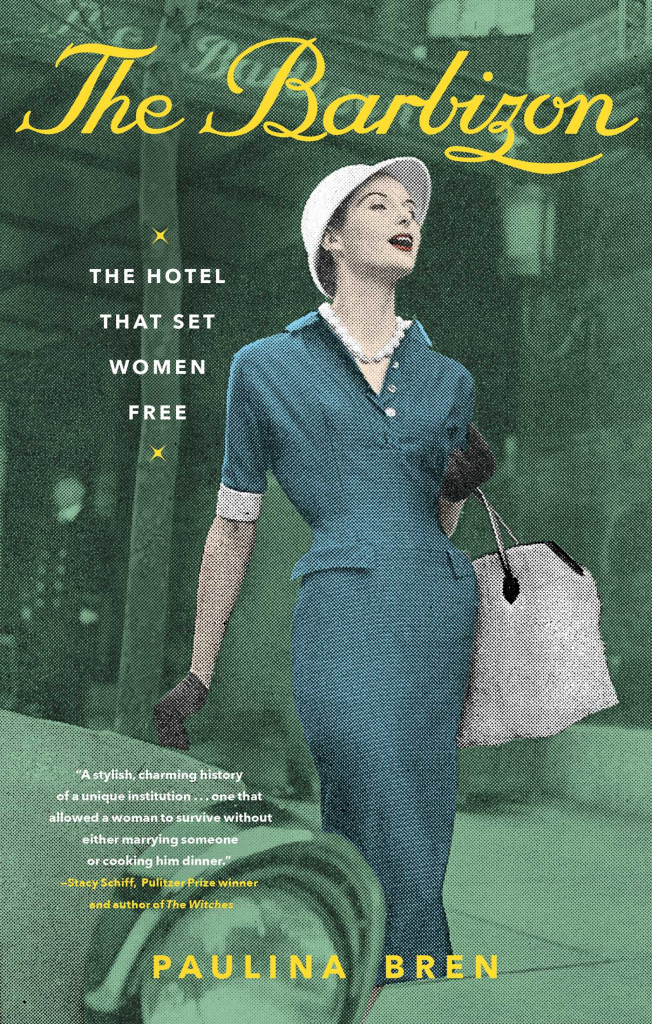

The Barbizon Hotel harkened to a different time in the Big Apple, one shown in movies like Breakfast at Tiffany’s and the TV show Mad Men-all glamour and fabulous clothes. So when I came across Paulina Bren’s book The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free, I knew I had to read it. And Bren’s book is chockful of fascinating history and New York City nostalgia that doesn’t exist anymore.

The Barbizon opened in the late 1920s. It was the age of the flapper with the Great Depression looming on the horizon. One of the first women to live at the Barbizon was the Unsinkable Molly Brown who survived the Titanic disaster. Interestingly enough, as progressive as Brown was (she was an active suffragist), she was not a fan of flappers.

Years before The Barbizon, women usually lived at home with their parents until they married or died. Or if you were Catholic, maybe you left in a nun’s habit. But by the 1920s, women had gained the right to vote. They bobbed their hair and shortened their hemlines. Before the Barbizon, young working women lived in boarding houses, which lacked the panache of places like the Barbizon. Women who lived at places like the Barbizon had an air of independence, prestige, and respectability (no men couldn’t go upstairs with their dates and had to meet them in the lobby). Barbizon survived the Great Depression and World War II when women needed to work and wanted to work.

But is was the 1950s and 1960s that is the Barbizon’s heyday. Though marriage and motherhood (and a house in the suburbs) were very important to women of that time, they still craved a sense of independence and some career success. Plus, the enchantment of the big city was a big pull. New York City was where anything could happen. You even might even meet your very own Mad Man.

Many well-known women spent their younger years at the Barbizon. The Barbizon boasted of women writers like Joan Didion, Gael Greene, and Sylvia Plath, the latter who wrote about an Barbizon-like place called The Amazon in her book The Bell Jar. Actors like Cybill Shepherd, Phylicia Rashad, Ali McGraw, Jaclyn Smith, and Liza Minelli lived at the Barbizon. And Grace Kelly called the Barbizon home just a few years before she left Hollywood and became Princess Grace of Monaco.

Relics of that bygone era like the Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School and the Powers Modeling Agency were affiliated with the Barbizon, which Bren does got into some length in describing them within the pages of The Barbizon. But it is Mademoiselle magazine and it’s connection to the Barbizon that is truly fascinating.

Mademoiselle was truly before its time. Published from 1935 through 2001, Mademoiselle covered topics familiar to other women’s magazines-fashion, beauty, and dating. It also published fiction by the likes of Truman Capote, Joyce Carol Oats, James Baldwin, and Barbara Kingsolver. Mademoiselle took young women and their aspirations seriously, and knew the importance of a woman’s education and career goals. From 1939 to 1980, Mademoiselle had a guest editor program. In the month of June, college girls (as they were called back then), descended New York City to take different editing assignments with Mademoiselle and they all stayed at the Barbizon during their tenure with the magazine.

Some of these guest editors had never been far from their hometowns other than college. Some had never been on a plane before and at times were overwhelmed by such a big city. But the GEs (guest editors) were thrilled to get a chance to work for such a prestigious magazine, competition was quite stiff for this plum assignment. And they were also excited about staying at the Barbizon and having adventures in Manhattan.

Some of the GEs included the aforementioned Sylvia Plath, Mona Simpson, Meg Wolitzer, and Diane Johnson. The GEs worked within various departments of Mademoiselle and not all were happy with their assignments. Some thought working with the fashion and beauty departments were beneath such serious scholars. But still, they were gaining a great deal of experience that eluded many other women of the time. Plus, the free swag, the excitement of the city, and handsome eligible bachelors were and added bonus to the program. Not surprisingly, most of the GEs in those early days were white and from middle to upper middle class backgrounds. One notable exception was Barbara Chase, who was a GE in 1956.

And the staff of Mademoiselle, which included its formidable editor-in-chief Betsy Talbot Blackwell, were titans in their field and a wealth of experience and knowledge. They were also a collection of headbutting egos. Perhaps the Devil didn’t wear Prada, but it did wear gloves, hats, and pearls. But at least the GEs were learning from the best in the business.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the Barbizon had seen better days. By the time of second wave feminism and yuppie excess, women were much more independent, making money, and wanted to be free of the shackles of the more protective clutches of the Barbizon. They wanted their own apartments where they could come and go as they pleased, and bring their dates back home to do whatever they pleased. Today the Barbizon Hotel is a memory of a bygone era. The hotel has been replaced by pricey condos.

I loved reading The Barbizon. Bren clearly loves the topic, and has put a lot research, craft, and care in making sure The Barbizon Hotel and its history is never forgotten.